There’s a growing belief that if U.S. automakers are abandoning Canada, there’s no longer any reason to do them favours

By Nojoud Al Mallees

As the weeks passed after General Motors Co. shut down the assembly line where he had been working, reality began to set in for Mike Horne.

Get the Latest US Focused Energy News Delivered to You! It’s FREE:

Sitting in a union office set up to connect laid‑off workers with training and employment resources, Horne, in his early 50s, was coming to terms with the idea that his job might never come back at the plant known as CAMI, about two hours from Detroit in the town of Ingersoll, Ontario.

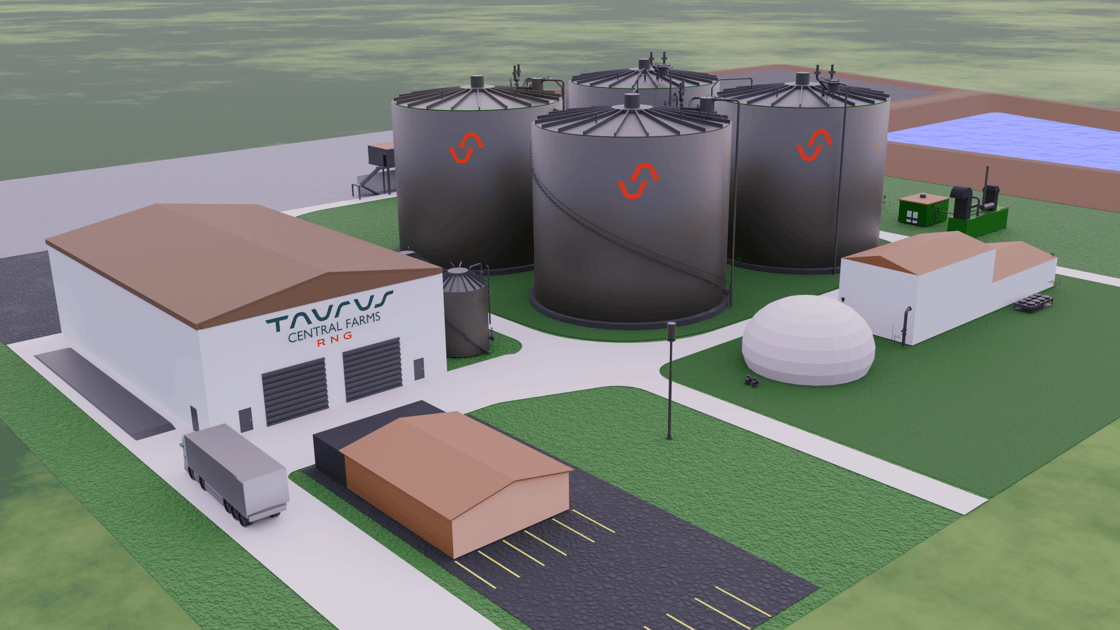

The factory once churned out hundreds of Chevrolet Equinox SUVs every day. For locals, getting a job there felt a bit like winning the lottery. But then GM took the Equinox out of the plant and switched it to making electric delivery vans that didn’t sell. Now, United States tariffs on Canadian-made cars and trucks make it hard to justify keeping it alive.

“It’s just time to get back out and maybe put CAMI in the rear-view mirror and focus on something else,” said Horne, who worked there for more than two decades.

He’s not the only one thinking about moving on. Canada’s long relationship with the Detroit automakers has turned fractious after the companies responded to President Donald Trump’s tariff policy by swiftly slashing jobs and production in Ontario. Industry Minister Melanie Joly has threatened to go after GM and Chrysler parent company Stellantis NV for money, accusing them of breaking past promises they made when they accepted government funding.

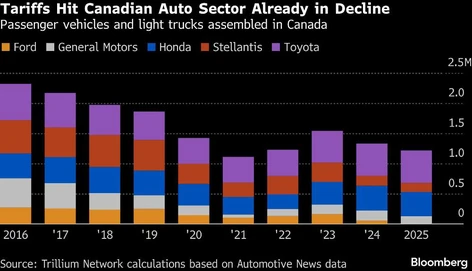

The companies sometimes called the Detroit Three — GM, Stellantis and Ford Motor Co. — used to dominate the Canadian automotive industry. But last year, they were responsible for just 23 per cent of the cars and light trucks made in the country, according to an Ontario research group, down from 56 per cent a decade ago. Two Japanese giants, Honda Motor Co. and Toyota Motor Corp., are now the firms that matter most.

And inside Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government, there’s a growing belief that if the big U.S. automakers are slowly abandoning Canadian factories, there’s no longer any reason to do them favours.

So Carney and Joly have done two things that would have been unthinkable just 15 months ago, before Trump moved back into the White House and began to say, over and over again, that he no longer wanted the U.S. to buy Canadian-made automobiles. They’ve gone to Beijing to court Chinese investment in the auto sector — opening up the future possibility of Canadian-made BYD or Chery vehicles roaming the streets of Toronto and Montreal. And earlier this month, they introduced a new automotive strategy with a proposed system of import credits.

It’s complicated, but the aim is to send a message to automakers: if you want to sell in Canada without paying tariffs, you need to make cars here. That’s a warning shot for companies like General Motors, which has the largest market share, selling about 300,000 cars and trucks in Canada last year. GM brings in most of those models from the U.S. — with the closing of Horne’s plant, it’s down to a single Canadian assembly plant making Chevrolet pickup trucks.

The Detroit automakers “rode their history for long enough that people still kind of thought, ‘Oh yeah, they make cars here,’” said Brendan Sweeney, managing director of Canada’s Trillium Network for Advanced Manufacturing. “And now we’re realizing that, no, they’ve kind of taken advantage of the situation and they’ve largely served Canada from elsewhere without really investing.”

The U.S. automakers have been cautious in their statements about the import-credits scheme. Brian Kingston, chief executive of the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association, which represents GM, Ford and Stellantis, urged the Carney government to focus on negotiating trade peace with the White House.

“While I understand the measures that Canada has taken in response to the U.S., we cannot lose sight of the fact that these tariffs should not be in place at all,” he said. “So I’d like to see a renewed effort to work with the U.S. and find a path forward here.”

Fortress Frictions

The Trump administration’s war on foreign vehicles is threatening the long‑term viability of Canada’s automotive industry, which has depended on the flow of parts and vehicles across North American borders — mostly tariff-free — since the 1960s. Carmakers face a 25 per cent tariff on the value of non‑U.S. content in vehicles shipped under the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement, meaning an Ontario-made sport-utility vehicle with 60 per cent U.S. components would face a 10 per cent tariff. In an industry of thin margins, even a single-digit tariff is a huge hit.

Many in the Canadian sector are sympathetic to Trump’s desire to have more auto assembly jobs in the U.S. But the real threat, they argue, is from China. Instead of pushing Canada and Mexico away, the three North American partners could work to reinforce the auto market with a new set of rules, said Rob Wildeboer, executive chairman of parts maker Martinrea International Inc.

Those might include higher levels of U.S., Canadian and Mexican content in vehicles and tightening up the complex “rules of origin” in the CUSMA. Failing to comply should result in higher penalties, he said.

This vision of a North American automotive fortress doesn’t seem to hold much appeal for the U.S. president. “They’re leaving Mexico and they’re leaving Canada,” Trump said at a news conference alongside officials from Stellantis, Ford and GM last year. “They took our businesses away from us. And now because of tariffs, they’re all coming back.”

Trump’s willingness to toss out the rules of continental trade has sparked a sense of betrayal among auto workers. Canadian taxpayers shelled out billions to help bail out GM and Chrysler during the global financial crisis and to help fund the retooling and building of plants.

Tariff tracker: Keeping tabs on the trade war

![]()

Source: Financial Post

“Trump is saying that all jobs need to come report back to the States. They were never his jobs in the first place,” said Mike Van Boekel, who served as the CAMI plant union chair when GM ended production of BrightDrop electric vans last year.

A spokesperson for GM noted the company has a history of more than 100 years operating in Canada. A renewed trade deal “will strengthen the global competitiveness of our integrated North American auto sector,” said Jennifer Wright.

Tariffs are particularly challenging for Canada relative to Mexico because it has a cost disadvantage on labour. Greig Mordue, an associate professor of engineering at McMaster University, said that’s partly why Canada’s auto industry has been shrinking for years, well before U.S. tariffs came into effect. The number of cars assembled in the country has steadily declined this century, falling from around three million in 2000 to 1.3 million in 2024.

The return of Trump “only brought urgency and visibility to an industry in decline,” Mordue said.

The parts sector is still a bright spot. The U.S. has shied away from putting tariffs on North American-made auto parts after warnings that doing so would cripple American auto factories.

Even so, Canadian parts-makers face pressure. Tyler Wood, vice-president of business development at Marwood International, described it as “very chaotic and exhausting” since the trade war began, as the industry adjusted to the stricter requirements for documenting products sent to the U.S. “We’re dealing with paperwork issues instead of trying to go get new work because it’s become such a challenge to manage just getting everything across the border,” Wood said.

The China Card

The Canadian government’s new auto strategy attempts to counter the tariff chaos by boosting financial incentives for carmakers to keep building.

When Trump first imposed automotive tariffs last year, Canada was one of the only countries to hit back with matching levies. Carney’s proposed new system would give automakers “import credits” when they make cars in Canada, which can be used to wipe out those tariffs or sold to competing companies. Honda and Toyota, as the two largest manufacturers in the country, stand to benefit the most.

The most controversial part of Canada’s new strategy is to chase investment from Chinese companies that make electric cars, which have been shut out of both Canada and the U.S. by 100 per cent tariffs put in place during the Biden administration. During his January trip to China, Carney also agreed to lower the tariff to around six per cent on a small quota of EVs — 49,000 a year — as part of getting China to reduce agricultural tariffs.

The deal has rattled some in the Trump administration, with Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick warning Canada’s deal with China could jeopardize CUSMA talks later this year. Automakers have also cautioned that allowing cheap Chinese EVs into the country could complicate the competitive landscape.

While Canada’s preference would be to maintain its historic partnership with the U.S. in the auto industry, Patrick Brown, the mayor of Brampton, Ontario, said the U.S. needs to realize that a permanent rupture in trading relations will force the country to forge partnerships in Asia instead.

Brown’s city has more at stake than most. It’s the home of a Stellantis plant that has been idle for years, with some 3,000 unionized workers laid off. The company announced plans to retool it to build electric and hybrid vehicles there, but in October it halted plans to start production on a Jeep SUV, giving that work to Belvidere, Illinois, instead.

“I have to assume that Chinese automakers, South Korean and Japanese automakers, are sipping champagne right now, watching the chaos that the Trump administration has created,” Brown said of the trade war. “And if those divorce papers actually happen, what other choice does Canada have?”

The head of Stellantis Canada, Trevor Longley, said the company is still in talks with the government on the future of Brampton. “We’ve been making cars in Canada for 100 years and we want to continue making cars in Canada for the next 100,” he said in an interview with BNN Bloomberg Television at the Canadian International AutoShow in Toronto.

McMaster University’s Mordue said the tariff agreement with China is unlikely to lead to profound changes in the Canadian automotive landscape on its own. The 49,000 EVs allowed into Canada at a lower tariff rate are less than three per cent of its new-vehicle market.

But if Canada wants to have a vibrant automotive sector, it will need an industrial policy that shakes up the status quo, he said. That includes making room for investment from China, which now makes more than 30 million vehicles a year, three times what the U.S. makes. It has also emerged as a global leader in electric vehicle production, building EVs at a much lower cost than its competitors.

Indeed, some U.S. automakers also seem to have concluded that there are deals to be done with China. Ford’s top executive spoke with Trump administration officials about a potential framework in which Chinese automakers could build cars in America while offering some protection for domestic companies, people familiar with the discussions told Bloomberg News. The idea involved Chinese carmakers partnering with U.S. companies through joint ventures in which the American company holds a controlling stake, the people said.

“If we keep our horse hitched to the U.S. automakers, our industry will suffer. It’ll suffer because of tariffs and it will suffer because of the increasing irrelevance of the U.S. automakers,” Mordue said. “People don’t want to hear that, but that’s where this is ultimately going over the medium- to longer-term, in the absence of more courageous action.”

—With assistance from Mario Baker Ramirez and Curtis Heinzl.

Share This:

More News Articles